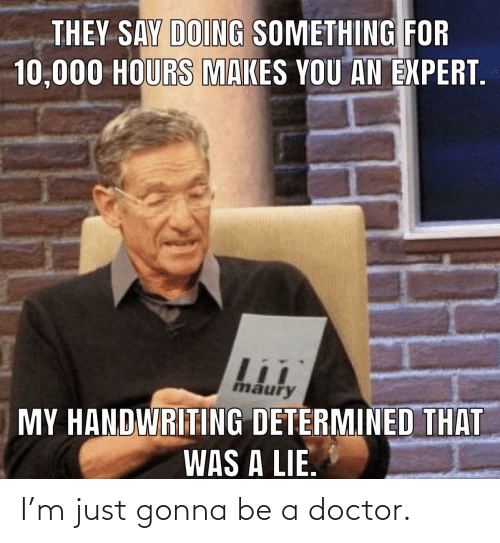

Curious Realizer - the infamous 10000 hours assertion

Revisiting Malcolm Gladwell's assertion that 10000 hours leads to greatness

I truly wonder if Malcolm Gladwell anticipated the reaction the following phrase would incite:

ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness

The question is this: does it take you 10,000 hours to become great at something? Is less (or more) required? What about merely being good or OK? Let’s dive into this controversial topic.

Note: I use terms like mastery, expert, genius, world-class, proficient and great(ness) somewhat interchangeably here.

Brief summary of the 10,000 hour assertion, with Gladwell’s examples

The concept of 10,000 hours to greatness (I refer to it as the 10,000 hour assertion) entered the zeitgeist in 2008 with the publication of Gladwell’s book Outliers. Gladwell summarized the research results of K. Anders Ericsson, a psychologist who researches expertise and human performance. In particular, Gladwell focused on research of top violinists who had put in an average of 10,000 hours of practice1 to master their musical skills and attempted to correlate that to historical wisdom about the time it takes to become great at something. He then offered a couple of other famous examples of years of work leading to greatness:

The years young Bill Gates spent mastering computer programming (also noting the benefit of Gates having access to a terminal with a keyboard at times when many programmers still had to use labor intensive punch cards to write and compile programs).

The Beatles became seasoned musicians after months of intensive live performances, especially during their Hamburg residencies in the early 1960s before Ringo Starr joined the band. Gladwell estimated that the core members (John, Paul and George) had performed together at least 1,200 times by 1964, when the Beatles’ fame really began to skyrocket. This did not include time spent practicing and songwriting.2

Criticisms of the 10,000 hour assertion

Gladwell has been criticized for a creative interpretation of the information at hand to come up with the 10,000 hours assertion. Other people smarter and more dedicated than I have done some detailed analysis to “debunk” Gladwell’s assertion:

David Bradley wrote an excellent rebuttal for the BBC in 2012, citing the original sources used by Gladwell in Outliers

In Talent is Overrated, Geoff Colvin dug into the concept of deliberate practice, which Gladwell did not discuss in detail in Outliers

In Peak, K. Anders Ericsson spent an entire book on the entire subject of excellence and made his own comments about where Gladwell misunderstood (or misinterpreted) Ericsson’s research and findings (summarized in this Salon article)

Examples of the hours required to become proficient

PROFICIENT: competent or skilled in doing or using something

There are many examples of careers and skills that need thousands of hours to become proficient in a discipline, here are a few:

In order to achieve the designation of Project Management Professional (PMP), one criteria is that an applicant must provide proof of at least 4,500 hours of related work experience (this is reduced to 2,500 hours of experience if the applicant already has a 4 year undergraduate degree).

To achieve a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy), a minimum of 8 - 9 years of study and research is required to achieve the required 3 degrees, many candidates will require more time.

What’s required to become a master or world class at something

A more complete list of characteristics, resources or steps to master a skill or a domain includes the following (and I welcome feedback on this list!):

Deliberate practice

Deliberate practice is the process of performing challenging practice exercises - done with many repetitions - so that a skill becomes imprinted in your brain and body. Music, sports, dance, martial arts, etc. are excellent examples of the need for deliberate practice. This is where terms like muscle memory and neural pathways get used to describe how this process works. Whether it’s practicing scales, jumpshots, Kung Fu forms or dance steps, repetition is a key component of skill acquisition.

A simpler, yet effective example of deliberate practice is weight training. You generally won’t get stronger if you lift the same weights the same way during every workout. You build strength by carefully pushing muscles to the point of failure, after which a combination of nutrition and rest will allow muscle cells to rebuild stronger than they were before the workout. Over time, your strength will increase.

One of the weaknesses of Outliers is that it does not adequately emphasize the need for deliberate practice, though it’s possible that Gladwell assumed that it was part of the process and felt he didn’t need to reemphasize it. Were the live performance experiences of the Beatles and the early exposure to programming really examples of deliberate practice? No, not in an academic sense but mastering a song performance or working through a computer programming tasks does bear some similarity to deliberate practice.

Coaching and timely feedback

Great coaches make good money for a reason. They are able to devise practice regimes, analyze performance and provide critical feedback to their students. The student often can’t evaluate their performance due to a lack of experience and objectivity. The student may complete an hour of practice on a Kung Fu form, as an example, but without proper coaching they might not realize that their left foot should have been one inch further to the left than it actually was, affecting balance and power during the form. The coach might detect a slight stumble at minute 55 that the student either missed or ignored, which needs to be corrected before it becomes an incorrect pattern that is incorporated into muscle memory.

Back to the examples of the Beatles and Bill Gates: did they get coaching during their performances/programming activities? The Beatles most likely did not receive coaching for their live performances; Gates may have gotten some hints from other experienced programmers.

But they certainly would have gotten feedback. The crowd (or the club owner) would have chewed out the Beatles if their songs were terrible. In the case of Bill Gates and computer programming, feedback is built into the process via failure: a computer program won’t work correctly if you haven’t written it correctly. Failure helps you get better through process of elimination, if nothing else.

A coach can also help the student with motivation and habits, as we’ll discuss next.

Desire and motivation, habits and routines

Desire usually appears at some point in the path to competence and mastery. Desire can compel you to start learning a skill and that feeling can provide the motivation to do the work needed to get better.

The true road to mastery is built on habits and routines, though. Desire and motivation can fade, especially since the progression of skills is not necessarily a linear increase over time and feels increasingly less fun for most people. The rate of skill acquisition often resembles plateaus and peaks, with some possible valleys. You can attain some proficiency in a relatively short amount of time. It may be possible to get to 25% - 50% mastery within a short time, to pull an example out of the air. The road from 50% to 75% could require significantly more time. And getting to 100% (or as close as possible)? A significantly longer period of time than the other two stages put together could be required.

And deliberate practice is hard work. It’s not meant to be fun. It’s meant to challenge you, so it’s designed to be difficult (but not impossible) as you work to get better.

Habits are the key to doing the work: never missing a workout, studying, eating a healthy diet, getting enough rest are habits that need to be built to push you to mastery.

Again, this is an area that Gladwell glosses over in his book.

Money and time

Mastery requires time, effort… and money. Like I mentioned earlier, professional coaching is often critical to skill development. Sports in particular require athletes to pay for equipment and instruction above and beyond coaching, plus travel to competitions. Fortunately, there are scholarships, bursaries and other types of funding available to help with the costs and depending on your ambitions there are decent free resources available to help.

Having the time available to devote to mastery can also require money. If you need to work a part-time job in high school to help pay for college (or, in some cases, just help your family to survive) you have less time (and money) available to practice. If you have to care for a sick relative or babysit your younger siblings because your family can’t afford to hire help then you lose time that you could use for practice.

I honestly don’t recall how much Gladwell wrote about these requirements (it’s been a few years since I’ve read Outliers), he probably assumed them to be self-evident.

Talent, physical advantages (possibly related to intelligence)

Colvin’s book Talent is Overrated, as you would expect, places less emphasis on innate talent and physical advantages than it does on deliberate practice. However, a person’s physical characteristics can have an impact on their ability to learn and master skills or, in some cases, provide a minimum requirement to participate. A basketball player’s height gives them a significant advantage for certain plays, there is no denying this. The ability to efficiently build muscle mass is an advantage for some athletes. Above average cardiovascular capabilities give runners, among other athletes, a significant advantage.

One of the key ways that Gladwell acknowledges physical advantages is in his assertions about young hockey players, providing examples of superior hockey players who are born in the first few months of the calendar year. His reasoning: being born a few months earlier than some of their peers gives young athletes to obtain more practice and training sooner, while also maturing physically earlier than their peers who were born later in the year.

As for innate talent… this is a tricky thing to judge and I’m not precisely sure where Gladwell stands on this. Can you be born with an innate talent for parkour, roundhouse kicks or the ability to code in Ruby on Rails? Seems awfully particular to me. More general abilities like the ability to learn quickly, good eyesight, good hearing and balance could be examples of innate talent.

Did Gladwell get anything right in his 10,000 hours assertion?

I do think that Gladwell was on the right track with at least some of his assertions in Outliers but I think he can be rightfully accused of exaggeration or favorable interpretation of information:

Is 10,000 hours a bare minimum amount of time to master something? “it depends”.

Is 10,000 hours a universally agreed upon measurement for attaining mastery? The answer is no, with a healthy helping of “it depends”.

Is practicing something for 10,000 hours a guarantee of mastery? The answer is no and I’ve described some key additional requirements earlier in this post.

What Gladwell did get right was to convey a sense of how much time and effort it takes to develop world-class skills. You can argue the specifics of what they did and how they did it but Bill Gates and the Beatles put a lot of time and effort into their work and they definitely improved their skills over the years.3

Is the 10,000 hours assertion important to you and me?

For most people, the 10,000 hours assertion may be interesting but it’s not going to change your life. The assertion, if you treat it as an iron clad rule, may unfairly discourage you from trying something if you think you need to spend 10,000 hours to become good at it. This line of thinking is the most damaging impact of Outliers.

You can have a lot of fun and enjoyment with a sport or hobby after a very small amount of coaching and instruction. In fact, with the free videos and articles available on the Web today you can literally learn some foundational skills of many hobbies within a few hours on your own. Writing, blogging, creating and sending newsletters, creating simple video can be started without 1:1 coaching and direction. You can learn some of the basics of piano, guitar or drawing without ever talking to another person.

On the other hand, if you want to become a world class athlete, a heart surgeon or a professional actor, it’s helpful to have a possible benchmark of the time and effort required to attain your goal. In that sense, the 10,000 hours assertion provides an order of magnitude estimate to consider, even though it won’t be 100% accurate.

It’s OK to be OK

But for most of us, for many pursuits, OK is good enough. You don’t need to be the best. You can try things and have fun with them as hobbies, maybe finding other enthusiasts to learn from. And even if you want to rise a bit above simple proficiency, you don’t need expensive equipment, world class coaching and unlimited time and money. You can thrash about on your own and have fun or try to find some help, it’s completely up to you.

It may well have taken Malcolm Gladwell at least 10,000 hours to become MALCOLM GLADWELL, best selling author and podcaster - there was undoubtedly a lot of blood, sweat and tears that got him to where he is today. But the world only needs one Malcolm Gladwell.4

The world also needs you and how your spend your time is up to you. Don’t fret about not putting in enough hours in something that’s not your career. Instead, spend your time developing habits and practices that suit your life and your goals; you’ll find the best fit for you.

And if you do want to be the best in the world at something… at least you have a rough order of magnitude of time and effort to consider.

The implication of the average is that some of the students would have reached the desired level of performance in less than 10,000 hours and others would have needed more time.

One of the trickier parts of using the number of times the Beatles performed as a measure of their proficiency is that the Beatles arguably demonstrated more than technical proficiency - the vast majority of the music they would have played in Hamburg would have been cover songs. The Beatles became famous for lyrics, songwriting and arrangements as well, as well as studio and engineering experimentation. Did it take them 10,000 hours to become proficient, if not masters in those skills too?

They were also very lucky at key points in their careers and may have had some advantages that helped them along the way (Gates’s early access to computer terminals and family business connections; John/Paul/George finding each other as collaborators and friends, plus other key collaborators like Brian Epstein and George Martin).

I’m prepared to acknowledge that one Malcolm Gladwell may be necessary.

I enjoyed reading this article, Mark. I thought it set out the different positions really succinctly. I don't know about other fields, but in education (or at least education in the UK), the 10,000 hour rule suffers from a double whammy.

Firstly, you have the original thesis by Gladwell, which is either a misinterpretation or, being generous, a catchy oversimplification of the research for popular consumption.

Secondly, some educators in the UK seem to regard the 10,000 hours rule as set in stone, thereby inadvertently misleading their students.

It reminds me of the craze of adopting a growth mindset. Lots of schools have done so, and yet Carol Dweck, who first wrote about it, said a few years ago that she had never come across a school that had actually adopted it.

I also think there is not enough emphasis placed on aptitude. For example, I am useless as DIY, but not too bad at writing. Therefore when we need decorating done, it makes more sense for me to write some articles in order to earn money to pay a professional decorator. The job is done twice as well in half the time. I am pretty certain that my spending 10,000 hours learning how to do DIY would be a waste of time -- not least because I find the whole thing unbelievably boring.

For what it's worth, my take on the 10,000 hours rule is that:

* Becoming an expert takes a lot of practice, training, and dedication.

* Directed practice is essential. To my mind, spending 10,000 hours (or whatever) practising the same task doesn't equate to 10,000 hours of practice, but one hour repeated 10,000 times!

This is a very true comment:

"The true road to mastery is built on habits and routines".

I completely agree with you, achieving that incremental change that takes you to the top 5% is heavily dependanr on strict routines and effective habits.